Framework for cosmography at high redshift

R. Triay [1] [2], L. Spinelli and R. Lafaye [3]

Université de Provence and Centre de Physique Théorique CNRS, Luminy Case 907, 13288 Marseille cedex 9, France

Accepted 1995 October 12. Received 1995 September 11; in original form 1995 June 29

ABSTRACT

We propose a geometrical framework which is adapted for the investigation of large-scale structures at high redshifts in curved spaces, within the standard world model of the Universe. It is based on the embedding of the comoving space into the 4D metric space, which provides us with a useful algebraic representation of the positions of objects in space. In particular, the interpretation and the calculation of geometrical quantities, such as distances between objects, angles, surfaces and volumes, become obvious. Moreover, elements of cartography provide us with a global view of the Universe which accounts for the curvature. A quasar catalogue is used for observational support. This framework is implemented in a routine called UNIVERSE VIEWER.

Key words: catalogues - cosmology: theory - large-scale structure of Universe.

1 INTRODUCTION

The investigation of the space distribution of large-scale structures (LSSs) and candidate formation theories is one of the main trends in cosmology at present. While Euclidean geometry suffices for describing the spatial distribution of available galaxy catalogues, it is clear that such an analysis when extended to quasar catalogues requires geometry of curved spaces because of the high redshift extent (Triay 1981; Fliche, Souriau & Triay 1982). The aim of the present paper is to provide an understandable framework for cosmography at high redshift. A useful definition of the comoving frame is given in Section 2, where the 'distance between quasars' is clearly defined (these objects are assumed to be permanent sources when their observation relates solely to an event, i.e. the emission of the observed photon in the past). An algebraic representation, which provides us with straightforward calculations of distances, surfaces, volumes, orientations, etc., is given in Section 3. Visual inspections of quasar distributions is a powerful tool for the investigation of LSSs and Section 4 gives a (distortionless) mapping of the Universe. The Burbidge & Hewitt (1993; hereafter BH) quasar catalogue (8000 sources) is used as support of our investigation.

It is clear that such a framework is useless if one limits oneself to a zero curvature space, as predicted by the inflationary scenario (Gliner 1965; Linde 1982). Such a scenario is not so clear cut, however, since the short extragalactic distance scale

2 THE WORLD MODEL

The basics of the standard world model are given in Weinberg (1972) and Peebles (1993). The geometry of the space-time

where

By defining the expansion parameter so that its present value

The space observed through the quasar distribution at redshift

where the coefficients are dimensionless parameters. One has the reduced cosmological constant

The Einstein equations provide us with the evolution equation

and the integration gives the expansion parameter

2.1 Distances and comoving space

Let

It turns out that the projection of photon world lines on to

where

For a dimensionless investigation of LSS, it is convenient to use a reference manifold of unitary curvature, where the coordinates are angles. Such a representation, which is not valid for a flat space, corresponds either to the 3-sphere

and is obtained from the metric of

and it is termed angular distance [4] (see equations 7 and 8). Hence, the angular distance of a quasar at redshift

Once the values of cosmological parameters are chosen, the quasars can be located on these spaces by using geodesic coordinates at the observer position

The formulas providing surfaces and volumes in the comoving space

and

For practical purposes one limits oneself to geocentric shapes (circles and cones), and one has

- an arc of a circle comoving radius, which extends over

radian ( for a circle), with a length equal to - the portion of a sphere extending over

steradian ( for a sphere), which has a surface area equal to ; - the volume by

3 ELEMENTS OF COSMOGRAPHY

For a flat space

3.1 Geodesic reference frame

A reference frame on

where

- the tangent vector to the geodesic

, which reads at the Galactic position on the geodesic identifies as a matter of fact to the line of sight ; - the Galaxy position (

) is given by the 4-vector where is the null 3-vector, according to equation (15), with ; - if

then a quasar at a distance can be observed over the whole sky (i.e., towards any line of sight ).

Let

Hence, according to equation (14), for any 4-vector

3.2 Calculation of distances and angles

The comoving distance

where the coordinates of 4-vectors

- for

, where is the scalar product in the three-dimensional Euclidean space ; - else if

,

Let

To avoid cumbersome calculations, it is convenient to choose a reference frame related to quasar

Hence if

and

where

Similarly, if

3.3 Euclidean neighbourhood

When using efficient 3D routines implemented on graphics-dedicated computers, it is interesting to have three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates of structures within their vicinity. Let us assume that the structure lies near quasar

The coordinate transformations can be calculated by using the group of

Let us denote

where

if

For the present purposes, the matrix

Therefore, the line of sight of quasar

where

It is clear that these formulas are in agreement with equations (26) and (27).

3.4 Non-singular embedding

The quasars positions on

see equations (16) and (14). Hence, one can easily check (by expanding the trigonometric or exponential functions at

4 CARTOGRAPHY OF THE UNIVERSE

The main difficulty in addition to that of geometrical effects is to disentangle real structures and artificial ones. It turns out that we obtain sensible results by using orthogonal projections of

The projections are designated by means index couples 'i-j' related to the 4-vectors defining the plane. These maps are classified with respect to geometrical properties in two categories:

- the edge-on views (0-i), with

. If then the whole Universe is projected on to the unitary disc, else within a unitary hyperbola, and is projected on to the edge of the map; - the face-on views (i-j), with

. The whole Universe is projected on to a disc, and is projected on to its centre.

In the following subsections, these maps are discussed regarding the distortion problem and the recognition of selection effects in observation. Let us mention that the selection effects depend either on the line of sight

4.1 Global views of the Universe

The coordinates of quasars

The zone of obscuration arising from the Galactic plane appears clearly when one chooses the north galactic pole (

4.1.1 Edge-on-views

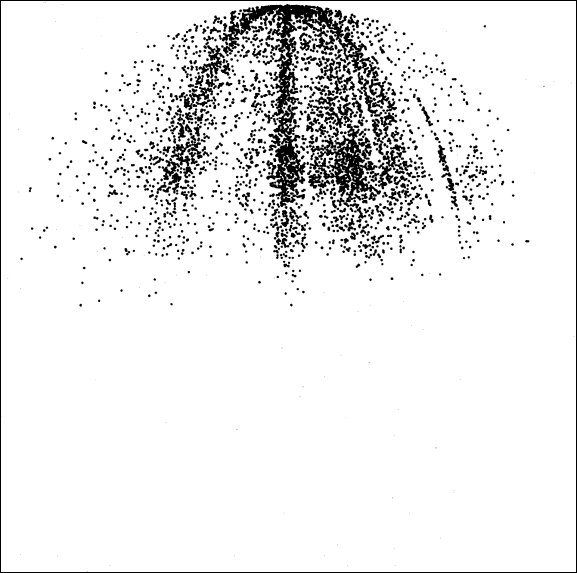

In the edge-on views [views

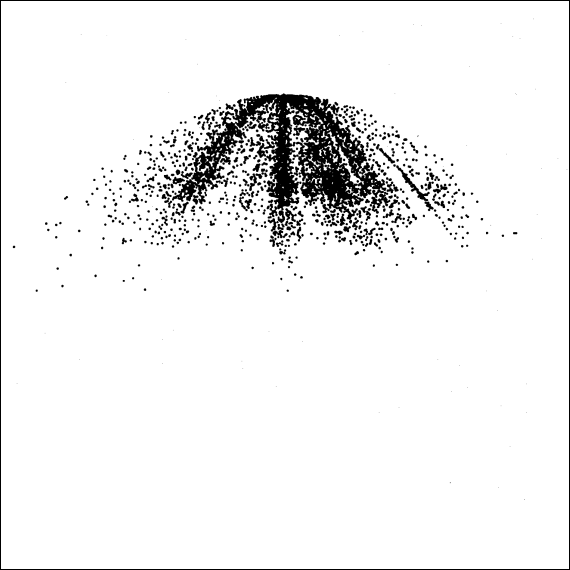

- If

then the quasar distribution lies within a unitary disc, since . In Fig. (1) the Galaxy is located at the top edge of the disc. Structures along the ellipses are selection effects which depend on the line of sight. The related equation reads where . The obscuration zone of the galactic plane is responsible for the lack of dots along the edge of the unitary disc (ellipse of unit ellipticity), since lies towards the North Galactic Pole. The horizontal structures along chords at constant (i.e., curves at constant ) are a result of selection effects on redshift. - If

then quasar distribution lies within a unitary hyperbola, since : see Fig. (2). Similarly, as above, the bogus structures owing to redshift selection effects lie at constant , while the selection effects on the line of sight lie along hyperbolae of equation .

[Figure 1] Edge-on view (0-1) of the Universe through the space distribution of the BH quasar catalogue, by assuming a positive curvature

[Figure 1] Edge-on view (0-1) of the Universe through the space distribution of the BH quasar catalogue, by assuming a positive curvature

[Figure 2] Edge-on view (0-1) of the Universe, by assuming a negative curvature

[Figure 2] Edge-on view (0-1) of the Universe, by assuming a negative curvature

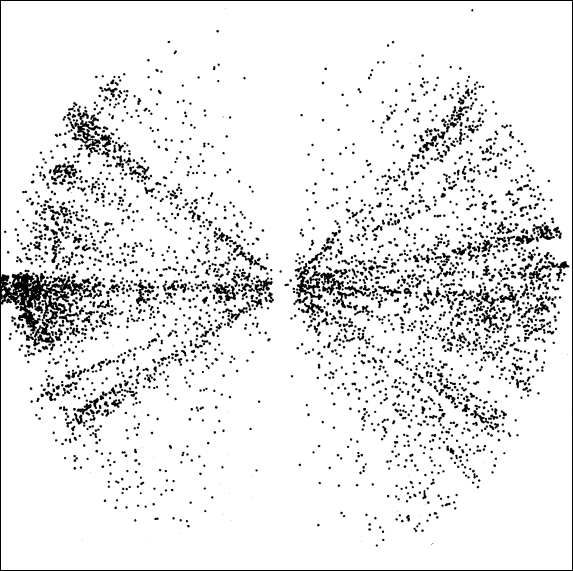

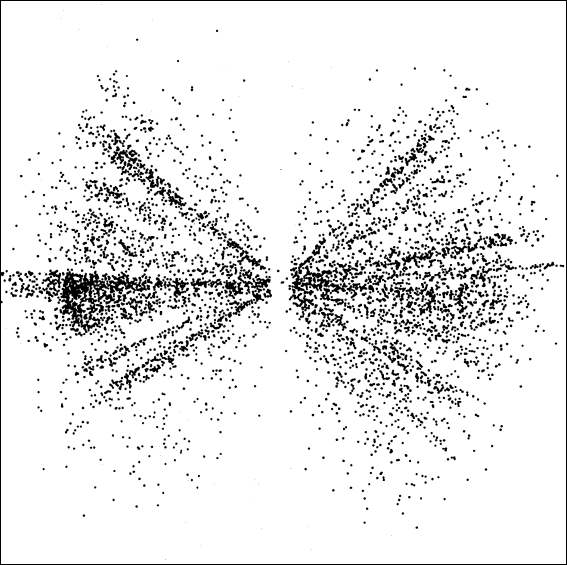

4.1.2 Face-on views

In the face-on views [views

[Figure 3] Face-on view (1-2) of the Universe through the space distribution of the BH quasar catalogue, assuming

[Figure 3] Face-on view (1-2) of the Universe through the space distribution of the BH quasar catalogue, assuming

[Figure 4] Face-on view (1-2) of the Universe through the space distribution of the BH quasar catalogue, assuming

[Figure 4] Face-on view (1-2) of the Universe through the space distribution of the BH quasar catalogue, assuming

4.2 About the distortion problem

The main problem for visual analysis is related to the distortion effect (e.g., as in maps of the world). To investigate such a problem we have to calculate the image of the volume element on

where

and the volume element may thus be transformed using

5 CONCLUSION

This paper introduces an efficient geometrical framework for the investigation of large-scale structures at high redshift in curved spaces. The world models are given by Friedmann-Lemaitre models of Universe. This framework is implemented in a free-share routine (Universe Viewer) developed on a Unix station, which is available on the internet network at node cpt.univ-mrs.fr/cosmology/UV.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Andrew Laycock for useful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Bigot G., Triay R., 1990, Phys. Lett. A, 150, 227

- Burbidge G., Hewitt A., 1993, ApJS, 87, 451 (BH)

- Carroll S. M., Press W. H., Turner E. L., 1992, ARA&A, 30, 499

- Fliche H. H., Souriau J. M., Triay R., 1982, A&A, 108, 256

- Gliner E. B., 1965, Sov. Phys. JETP, 22, 378

- Linde A. D., 1982, Phys. Lett. B, 108, 389

- Peebles P. J. E., 1993, Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton

- Pierce M. J., Welch D. L., McClure R. D., Van den Bergh S., Racine R., Stetson P. B., 1994, Nat, 371, 385

- Souriau J. M., 1974, in Colloques Internationaux du CNRS, 237, 59

- Souriau J. M., Triay R., 1995, Phys. Rev. D, submitted

- Triay R., 1981, thèse 3ème cycle, Université de Provence, Provence

- Van den Bergh D. A., 1991, in PASP Conf. Ser. 13, The formation and the Evolution of Star Clusters. Astron. Soc. Pac., San Francisco, p. 183

- Weinberg S., 1972, Gravitation and Cosmology. John Wiley & Sons, New York

- Wilkinson D., 1991, in Blanchard A., Celnikier L., Lachièze-Rey M., Trân Thanh Vân J., eds, Rencontres de Blois 1990, Physical Cosmology - Proc. 25th anniversary of the Cosmic Background Radiation Discovery. Editions Frontières, Gif sur Yvette, p. 97

The European Cosmological Network ↩︎

E-mail: triay@cpt.univ-mrs.fr ↩︎

Stage Informatique du DEA de Physique Théorique 94/95 ↩︎

To avoid confusion with notations given in the literature, let us write the RW metric as follows:

where

is the sign of the curvature, and if it is not zero then , otherwise and finally one has the radial coordinate ↩︎ For example,

( , ), is given by a rotation of angle about of a unitary vector , and . ↩︎ Indeed, the first one is related to surveys sampling, such as pencil beams, ..., when the second is based on spectroscopic criteria, such as the chromatic sensitivity of receivers, ... The identification of main emission lines Mg II, Ly

N v, C III, C IV, Si IV, ... is possible when they lie within the observable wavelength range. ↩︎ Indeed, a region of the Universe at redshift

is projected within a disc of radius given by if or if , which does not indicate the distance. ↩︎ Applied to the case of

sphere projected on to a diameter (one-dimensional disc), it is a well-known theorem. ↩︎ In other words, the image of the uniform measure on

is still uniform. ↩︎